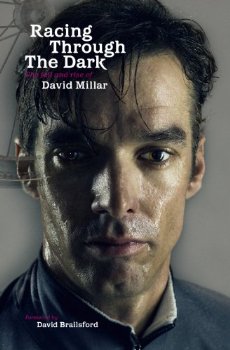

Reading the excellent autobiography of David Millar. It’s so well written that you have to make yourself stop reading so that it isn’t finished too quickly.

What I’ve found to be amazing is the account of the reality of the difficulty of recovering from training. Despite Millar being only 20 at the time and at an elite level, his doubts and tiredness levels reflect exactly the same basic problems that are encountered by someone taking up the sport at age 50.

I’ll never forget the 2001 Alpe d’Huez stage of the TdF when Lance Armstrong feigned poor form all day and then blew everyone away at the finish. It’s shocking to read what was simultaneously happening to David Millar and how on that day not only did he have to abandon the race but a Cofidis team manager exploited his complete breakdown to turn him into a doper. The insidious way that it happened makes for classic reading as you can feel the shift of mindset yourself. Very scary!

Cross Training

Back on the Bike again and another good workout. I was a bit apprehensive with the blisters on the feet still being a bit lively but they had no effect on the cycling. That’s the great thing about cross training. I resisted the temptation to puncture and drain the blisters because the liquid seemed to be getting absorbed very quickly. That was a good move because today (day after this workout) they have completely drained naturally and the thick skin remains intact for protection. I’ll be running on them again in a day or two – but not totally barefoot for a while! The idea will be to try to take the timing lessons from the long barefoot session and apply them to running with minimalist shoes – and also to think about the inefficiencies that produced the friction that caused the blisters. The blisters were worth it because it proved to me that I can run with no heel strike and have absolutely no calf pain either during or after the run – even over 10k and with some speed work.

Training Effects

The circuit around Granier is always very revealing with the short 520m (1700ft) climb at the start. This year – my second proper season of racing – has been a period of self discovery concerning the effects of training. Unlike David Millar I’ll thankfully never have the pressure to recover from training that requires the use of drugs. I refuse even to take painkillers for that purpose though they would certainly assist sleeping and initial recovery after particularly hard workouts or races. The only thing I concede in this respect is to drinking lots of coffee. This year I pushed much harder in training in terms of distance covered and time in the saddle – but to no apparent benefit. All of the workouts were in the mountains and the longest sessions stretching to over 10 hours. Granier was often the first or second short workout afterwards or sometimes used as a short workout prior to a race. The variation in performance on this climb became more and more informative as the season progressed. It has fluctuated across a range from 38 minutes to 31 minutes. The slowest times didn’t reflect the poorest form – they reflected lack of recovery – and sometimes this would be a full week after a hard workout – there would still be no basic energy available. I wouldn’t even be aware of it until realising that on the climb there was just no way of going any faster. My PEL (perceived effort level) would feel pretty much the same each time – so it shows that subjective monitoring of training is not very effective. It took me a long time to realise that lack of recovery was constantly affecting me and had affected me all summer. With October here and a big decline in long tiring workouts, giving much more recovery time and a focus on shorter more explosive workouts, my times have generally dramatically improved. With a cold (no warm up) and slow start yesterday I recorded 31 minutes with an average heart rate of 159 which is excellent for this climb. Attempting a PB of just under 30 minutes would require an average heart rate of around 169 and a flying start with the muscles properly warmed up.

The circuit around Granier is always very revealing with the short 520m (1700ft) climb at the start. This year – my second proper season of racing – has been a period of self discovery concerning the effects of training. Unlike David Millar I’ll thankfully never have the pressure to recover from training that requires the use of drugs. I refuse even to take painkillers for that purpose though they would certainly assist sleeping and initial recovery after particularly hard workouts or races. The only thing I concede in this respect is to drinking lots of coffee. This year I pushed much harder in training in terms of distance covered and time in the saddle – but to no apparent benefit. All of the workouts were in the mountains and the longest sessions stretching to over 10 hours. Granier was often the first or second short workout afterwards or sometimes used as a short workout prior to a race. The variation in performance on this climb became more and more informative as the season progressed. It has fluctuated across a range from 38 minutes to 31 minutes. The slowest times didn’t reflect the poorest form – they reflected lack of recovery – and sometimes this would be a full week after a hard workout – there would still be no basic energy available. I wouldn’t even be aware of it until realising that on the climb there was just no way of going any faster. My PEL (perceived effort level) would feel pretty much the same each time – so it shows that subjective monitoring of training is not very effective. It took me a long time to realise that lack of recovery was constantly affecting me and had affected me all summer. With October here and a big decline in long tiring workouts, giving much more recovery time and a focus on shorter more explosive workouts, my times have generally dramatically improved. With a cold (no warm up) and slow start yesterday I recorded 31 minutes with an average heart rate of 159 which is excellent for this climb. Attempting a PB of just under 30 minutes would require an average heart rate of around 169 and a flying start with the muscles properly warmed up.

Other than becoming aware of the how slowly the body recovers from long endurance work I’m not sure what other lessons are to be learned here – it’s all a bit foggy. Will the body adapt to long endurance high speed efforts over a period of years, or is it a waste of effort to do long training sessions? Repetitive strain injuries from the long workouts taught me that there was something wrong with my technique and so I eventually worked that one out. I can probably marginally improve on my personal best times from last year – but only just and perhaps those improvements are due to technique. I’m really not sure if the long workouts bring any real benefits. You don’t lose any weight with them either because you end up eating more to compensate. One thing I have noticed is that with so much long endurance work I’ve never once been able to get my heart rate up to its maximum all season – reaching around 10bpm short of the maximum at best. The only real advantage seems to be psychological – in that everything else seems like a short workout now.