Well, I never imagined in a million years that I’d ever be congratulated by Bradley Wiggins – sporting superstar, Olympic champion, World champion and World record holder! Yesterday however it happened. His congratulations went out to all of those who finished the Étape du Tour from Issoire to Saint-Four in the most horrendous conditions.

“Dantesque” is the word French journalists have used to describle the second Étape du Tour 2011 in the Auvergne region of France.

Dante’s “Inferno” (Italian for “Hell”) doesn’t loom large in the English language culture so we might describe it more appropriately as the “Étape out of Hell”. The attrition on the field of participants throughout the day was spectacular. 6500 People had paid anything from 75€ to 500€ to participate and had travelled from all over the world – with only 4056 making it to the start line. The horrendous weather had completely discouraged many from even starting – and those who did get this far were soaked in a torrential downpour at 06:20am before even arriving at the start line. Of those starting over 2000 would abandon with only 1982 making it to the finish line, some 211km (131 miles) and 3800m climbing (12,467feet) away over the Massif Central mountain range in the middle of France. This is the same Tour de France stage that saw carnage last week with a television car knocking two riders off the road and one being stopped at high speed by a lacerating barbed wire fence. Alexandre Vinokourov fell on a descent and smashed the top of his femur in a career ending accident. That all happened in good conditions but today it was the most violent weather that nature could manage to throw at us. With the first turn of the pedals at the start nobody imagined what they were heading into. For those who finished there were tears of relief from some as exhaustion and cold had stretched them to their limits with an average finishing time for the survivors of around 09:40h.

General ambiance…

Open for larger images…

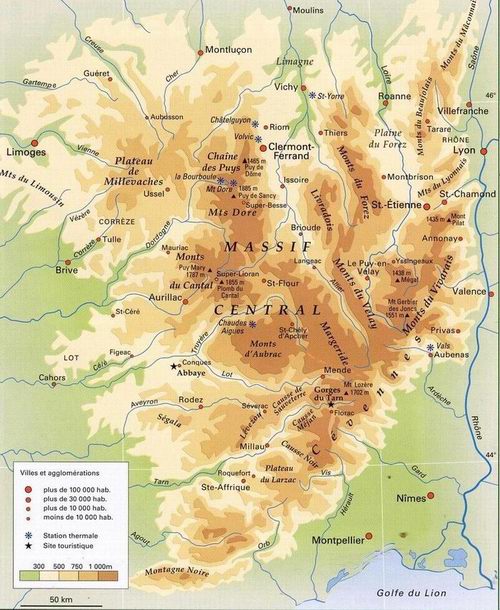

Course map and Mountains

Auvergne is a large administrative region of France and we would enter 3 of its 4 departmental areas – starting in Puy-de-Dome(63) then Haute-Loire(43) and ending in Cantal(15). Mainland France has 22 administrative regions and 101 departments. People living in France come to recognise the departmental numbers. Val d’Isère, Tignes, Les Arcs, La Plagne, Courchevel, Meribel are all in Savoie – department 73.

Interactive course map/satellite views (track recorded from my Garmin GPS unit)

We started off at only 400m altitude and were lulled into a false sense of security by the wet but still clammy weather. The heat from the previous day had not yet completely drained away so it appears that everyone had decided that it would be a typical wet summer day in “middle mountains” – which is tolerable and even enjoyable. How wrong we were! This initial error was only reinforced by the first 40km which didn’t climb much in altitude. At this stage the rain and wind were as expected and despite the chill of them on the body there was nothing drastic to deal with. I ended up in a peloton that grew in size and speed as it collected more along the way and eventually came across some of Chris’s American “

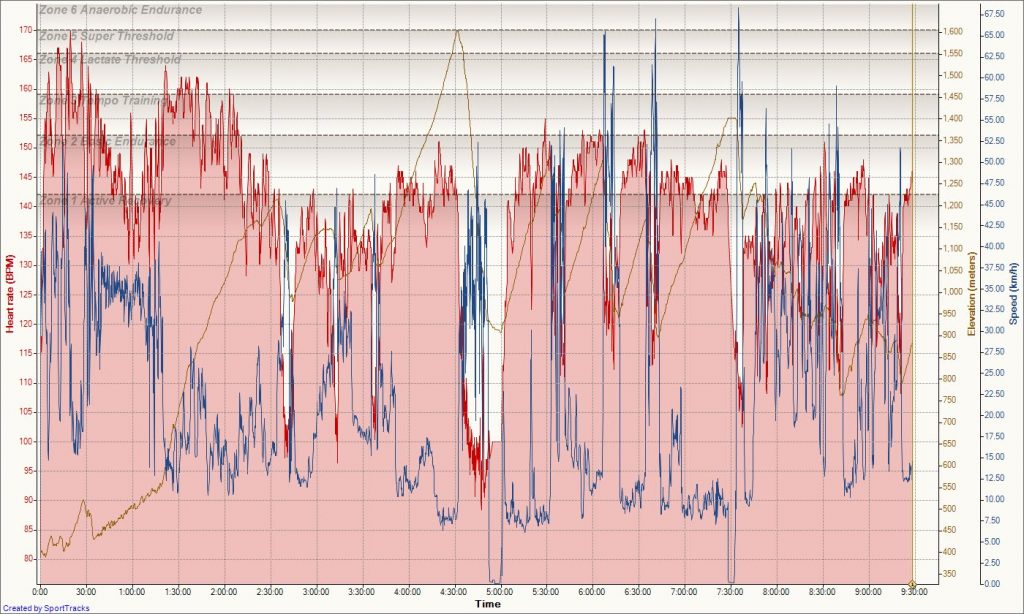

Bethel Cycle” guests basically trying to shelter from the elements in another peloton. I heard the name “Greg” and remembered that he was the organiser of the group – but I was too much in survival mode already to go over and try to remind him of our previous encounter at the top of the Col de la Madeleine a year earlier in much better weather. When we arrived at Massiac just before the first real climb there were a couple of really tricky obstacles to negotiate including lethally slippery railway tracks and an narrow wooden bridge. The marshals (all volunteers) did a great job of slowing everyone down and preventing accidents. The climb up the La Côte de Massiac was still okay because no-one knew what was coming and it only took us up to 753m altitude. We continued upwards entering properly into the nightmare. The climb continued directly into a powerful headwind and sometimes crosswind with torrential lashing rain and at times hail. Even the motorbikes of the organisation reported having trouble staying on two wheels. Reaching the “Plateau du Bru”, commune de Charmensac at 1000m altitude conditions had become simply brutal. The temperature had plummeted to 2°C. The only other times in my life I’ve witnessed such conditions is winter in the middle of the North Sea. I was clearly under-dressed with only a jersey and thin transparent semi-waterproof layer with fingerless gloves, shorts and no hat. Fortunately I’d put on shoe covers – and arm warmers at least – but everything was soaked through and not functioning as insulation. It was really difficult to find a proper group to work with – the hills and troughs causing all sorts of accelerations and braking up any team work. This section was about 16km long and climbing to the Col du Baladour at 1209m altitude. I ended up doing large chunks of it on my own and eventually found myself in a slow massive peloton where everyone was huddling together for shelter. It was disappointing to slow down so much but by this time it was very clear that racing mode had now been swapped for survival mode. In the hour that this hell had been going on my heart rate on strong efforts had dropped from 160 to 140 bpm and although at the time I thought that it was a lactic acid issue it must have been due to the body core temperature dropping too low. Along the Plateau du Bru it had become clear that people were caving in to the conditions in droves. Just about any object or building that could provide shelter from the wind was being used with bikes lined up and people huddled out of the wind. In villages people had been opening their doors to cyclists by the dozen and giving them towels to dry themselves and cover themselves with. Some cyclists simply stopped at the side of the road holding onto their bikes unable to move – paralysed. The ambulances of the emergency medical team were full and couldn’t help them. Others were being helped at the roadside when obviously overcome with hypothermia.

Perhaps the most surprising thing was the large number of people standing at the road side in all the villages cheering everyone on despite the atrocious weather. Really it made a difference. Their shouts of encouragement and appreciation seemed to refocus the positive side of things and help to avoid being engulfed completely by the apocalyptic and seemingly unreasonable conditions. Up until this point I had only to deal with painful wind and rain lashing the body, the legs starting to tie up with the cold and my core temperature dropping to uncomfortable levels. Descending towards the first feeding station at Allanche was to elevate the torture to another level. Already I’d discovered that eating was not an option because I couldn’t use any fingers well enough to access anything in the pockets. Drinking wasn’t an option either because the water bottle was immediately falling out of my hand due to lack of control. The descent amplified those problems 10 fold. It wasn’t a long descent but it was just long enough to hurt. Brakes had to be used the whole way and that starts to become difficult when your whole body spasms violently shaking itself to generate more internal warmth. Concentration is hard when your core temperature is low and you have reached borderline hypothermia. You can’t actually feel your brake levers but you can hear and feel that the brakes are working. The French got it right when the put the rear brake on the right – because the left hand fails first. Arriving at the bottom, jaw shaking in tremors and teeth chattering noisily I didn’t stop because I knew I wouldn’t start again if I did and anyway I still had all my food and liquid on board – practically untouched so why stop? In Allanche there were already several large buses completely full of cyclists who had abandoned and the shops were packed out with them too – over 30 in the butcher’s shop apparently! The village hall was opened as an emergency response to shelter cyclists. Some – like those in Chris’s group managed to team together in Allanche and find another more direct route to take out of the hills and weather and directly to the finish – in that case using an iPhone navigation that someone had in his pocket.

Just prior to starting in the morning someone next to me said to me “Pas des bidons?” Which means “No water bottles?” and when I looked down I realised that unbelievably the water bottles and energy mixes in them had been left behind! Worse still the first feeding station wasn’t until kilometre 70. Handing my bike to someone I jumped over the fence and into an open cafe to buy a small bottle of water and can of Coke – which unfortunately were icy frozen but at least would fit into a pocket. Meanwhile my new companions went on a search and found two people who were discarding extra bottles prior to starting the race and they handed them to me – a real life saver! Thanks guys whoever you were!

Notice the sunglasses in place in the helmet – the eternal optimist! (or just naively unprepared?)

At Allanche we were in a valley and there was some protection from the elements – enough to allow me to drink and eat just a little after warming up by climbing again. Ahead the view was rather disturbing because we still had the high peaks to come – some 400m higher – and the weather looked even more closed in and worse. I kept in mind that Paul had said the wind would not be directly in our face after 64km (which I’d obviously picked up on wrongly). I hadn’t studied the course and actually had no idea that it had 3800m of climbing – but just convincing myself that the conditions would change and the weather forecast was for a steady improvement was an important mental strategy. After Allanche there was a lot of climbing and not much descending so that stopped things from getting any worse but my heart rate dropped down to the low 130s and low 140s even when climbing now – only 3 hours into the race! That was definitely not a lactic acid problem! It was difficult to see how it was going to be possible to finish this race and basically the worst was still to come.

The Col du Pas de Peyrol at 100 kilometres was the highest point where we were properly buried in the dark clouds. After the Peyrol would be another feeding station but not before a terrible 22 minute descent with the brakes held on all the way. Knowing that this descent had ended Vinokourov’s career a week earlier didn’t make it more pleasant but it probably helped maintain concentration a little better through the mental fog of mild hypothermia. My left hand was now regularly slipping off the brake involuntarily and I had to work at clamping it back on. The fingers might not be working well but globally the hand could still work. Unfortunately now this hand could no longer manage to change gears so the right hand had to be used to change gears on both sides. There were moments when I wondered if I might just not be able to feel what was going on and just fall off the bike – but that never happened. I saw it happen to someone else when his gears started to slip on a climb and he completely keeled over on his side. The next feeding station was at the bottom of this descent at Mandailles-St-Julien and failing to stop here would have been pure madness. This was another “war zone” where the village decided to open some old school buildings to shelter cyclists who couldn’t continue with the race. Early in the morning the volunteer staff had problems of their own when the big tent for the feeding station was blown clean over by the wind as they struggled to prepare for the day ahead.

Despite the scale of all this chaos it wasn’t us making the news headlines in France. That honour was reserved for another group of cyclists on the Col du Galibier. Between 150 to 200 had to be rescued and and taken into the fire station in la Grave to be warmed up and then bussed off the mountain. Attention was squarely on them because the Tour de France double crossing of the Galibier is due this week and the weather is expected to stay bad with snow falling at altitude – although not staying on the roads. The cyclists likewise were not blocked by snow they just couldn’t manage to descend in the cold. The temperature in the Alps however was a couple of degrees warmer at 4°C despite the higher altitude. Apparently the Massif Central is often one of the coldest areas of France – at least in the winter.

It was now 113km and I was stopping for the first time. Getting off the bike and standing on my left leg the leg partially gave way – not through tiredness but though dysfunction brought on by the cold. I immediately started to stuff myself with food now that my hands could be used without the obstacle of managing the bike. Even drinking a luke warm tea with chattering teeth and shivering body didn’t pose too much trouble. Others were simply unable to hold a cup steady enough to drink. The food was appreciated because I was hungry by now and it was much better eating real food than gels and sugary bars. A fresh banana was much appreciated. Although this was already a much longer stop than I’d normally permit it seemed reasonable under the circumstances and so I took the time to go over to an embankment for a pee. First of all my body was not cooperating and the pee seemed to never want to start then by the time it came my core was shivering so violently that the pee was being sprayed all over the place. One guy standing behind me shouted over in French ” Careful not to pee on the bike”. “What bike.” I answered. “The one behind you!” Humour aside there was one moment I was shaking so violently that I appeared to have trouble breathing – but that passed quickly.

My brain was lucid enough to recognise that the violent shivering was to warm up – so as this was getting worse it was obvious that the best solution was to get back on the bike and attack the next hill. The start of the Col du Perthus was steep but the short break had allowed everything to recover to some extend and attacking hard at the start got the body warmed up very quickly and the shivering stopped. This was the turning point for me. There were still four significant climbs ahead but the air was warming a bit and the hands never failed again. My feet and body remained freezing until close to the finish but that was not so important. Despite feeling less endangered there was no great improvement in heart rate which was maxing at 150 on the climbs (my actual max hr is 185) but it was still higher than when the cold was at its worst. One person standing at the roadside had counted every cyclist passing him and was shouting out our placing to us. This was very useful because when he said 938 to me I decided to defend that position and make sure to overtake more people than would overtake me from now on. Anything to generate a positive focus and try to maintain some reasonable level of effort. Physical tiredness was now creeping in and my lower back was complaining although not violently. Apart from a brief period of stomach pain – somewhat like a stitch – there were no digestive or persistent stomach issues like there had been on the two previous races. This is encouraging because digestive problems had been quite significant on those occasions. The final category 2 climb of the Col de Prat de Bouc was at 156.5 km. I had no idea what lay ahead so I asked someone and he assured me that it was the last big climb – which we both agreed was good because our legs were hurting. That gave me a new lease of life and I dropped the other cyclist. All day the same pattern had been evident – I’d lose ground on those around me at the start of each climb and then reel them back in again at the top and often go way past them. It’s like the brain would give me permission to go when it knew it was safe. The very top of the col decided to give one final vicious blast of wind – the worst of the day – before we could turn out of it to head for the finish line.

Depassement

The French have a great word to describe “going beyond your perceived limits” it’s called “depassement”. English doesn’t have an equivalent word that can be used in this context – and that’s a great shame. This particular day was 100% about “depassement”. The beauty of this process is that it isn’t about the cold, the heat, the physical discomfort or the effort – it’s about recognising that internal dialogue that says “you can’t” and turning it into “you can”. There’s an infinite number of ways, direct or insidious that this negative dialogue creeps up on you – but it’s always the same dialogue. It tries to convince you that it is logical, reasonable, objective and reality. The magic is in breaking that spell – and doing it without resorting to amphetamines or any other artificial aid. My own process involves scanning my body and feelings, asking frankly what the level of discomfort really is. Invariably, when you apply your attention directly to your body like that, you realise that it is not nearly so bad. The internal dialogue is led by fear and doubts and it exaggerates things to protect you – but often it goes way too far and leaves too big a margin of security. People being afraid of needles/injections is a good example. We were close to the edge today that’s for sure – but that’s what makes it memorable and valuable. This race was a success for those reasons despite the overall party being spoiled.

Energy levels seemed to fluctuate during the multiple remaining climbs and descents until eventually I ended up accelerating and catching onto the rear of a passing train. Sticking with this bunch created the drive and motivation to keep on working and pushing hard – lifting me a bit more out of the doldrums. The descents were now drier, warmer and much faster and so more enjoyable. One village we went through there was an old guy sitting outside a garage who had rigged up some sort of air horn connected to a compressor that sounded like a shockingly loud cow – and he was taking great delight in letting it off each time someone passed. He did manage to raise a laugh inside me and even miles further on you could tell when another cyclist had gone past him. The welcome and encouragement in all the small villages was amazing with a real party atmosphere. They were as determined as we were to overcome the adverse conditions. Eventually some faster people hijacked the peloton and another longish section was spent more or less alone or trying to work with apparently uncooperative individuals. There were many less people on the road than we had anticipated so it meant that it was fairly easy to become isolated. The wind was generally behind now and there was more descending than climbing so working alone wasn’t too bad.

The arrival at Saint-Flour was a steep categorised climb up a volcanic plug by the look of it. I had just caught up with someone who was determined not to let me get ahead. When arriving at the 2km to go sign my brain did its trick and let me go again, accelerating from 10 kph to 12.5kph and then 13.5kph for the last kilometre and the climb right to the finish line. Getting off that bike was just great – the best moment of the day. The staggered start in the morning had taken 45 minutes – me being in the 6th group out of the gate – but the finish was over instantly.

Epic

I immediately stuck the bike in the security pen and went to look for food. Amazingly a local dish was provided that included hot stodgy cheesy potatoes and a good quality local regional sausage. Hot stodgy food was exactly what was required – for once the organisers had managed to get it right! Although it was still cold the the warm food had a good effect and then the sun came out for the first time – progressively massaging the body back to life with its powerful rays. The finish area was obviously a bit less busy than had been planned but there was still a big screen following a sprint finish stage of the Tour itself and I saw the last five minutes and Mark Cavendish capturing another stage. Luckily for the Tour riders today they were on lower ground and down south near the Mediterranean. I called Paul who was still in the finish area and we met up to decide how to get down to the car parked below. Another small tour and we were at the bottom and safely changing into warm dry clothes at last. Paul described the étape as “Epic!”. I think that my choice of words was more graphic but won’t repeat that here.

210.5km 3800m Climb, 8 Categorised climbs.

6500 Registered, 4056 Starters, 1928 Finishers.

Tour de France stage winner: 05:27:09

Étape1st place 06:48:55

Chris Harrop 08:37:17 overall position 307th, age cat(1952 to 61) 50th

Paul Evans 08:39:40 overall position 322nd, age cat(1952 to 61) 55th

Me 09:28:13 overall position 858th, age cat(1952 to 61) 177th (474 in cat)

Median Time 09:40:00

Last 11:31:16

Madone Challenge

Over 1000 racers participated in the Madone Challenge – the combination of the two separate amateur Etapes of the Tour de France. Only 314 completed the challenge.

My placing was 148th in 14:58:02 hrs.

Chris Harrop 69th at 13:36:19 hrs

If it takes bad weather to weed out the competition then that’s fine by me – bring it on. I’ll be even better prepared in future.

Conclusion

I think Paul surprised himself because he wasn’t too confident before the start. A combination of good preparation and conditioning brought him a great result and he enjoyed the race. Nobody can ever argue with placing 322nd in an étape let alone overcoming all of the exceptional difficulties of the day. In some ways the conditions perhaps played to Paul’s strengths and experience in dealing with training in Scotland – but that’s all to his credit.

I was laughing to myself during the day because I know how much Chris hates riding in the rain and how he is affected by the cold – but also to his credit he didn’t bail out – and I wouldn’t have expected anything else. Another good time with a consistent distance ahead of me in relation to other recent races.

Me? I’m happy to have stuck it out. There was a lot of learning today and a lot of mistakes made – especially the under-dressing and not studying the course in advance. My low heart rate was weird and I’ve never seen that before. A recent workout of similar distance and climbing had me able to sustain 155 bpm on all the climbs – so something went wrong here today. Only part of the race and a few moments were enjoyable – the rest was pretty hellish – but that’s quickly forgotten. It’s hard to draw any specific conclusions except that I need to get fitter. Perhaps not getting sloppy and fat over winter months might help in future. I’m a relative beginner in this field and should probably be very happy with the results, knowing that it takes years to build stamina. No musician masters an instrument or skier develops excellence in such a short time so this shouldn’t be any different. Like for today itself – “persistence” – is the message.

Click to enlarge…

Organisation

Paul was in the area of Issoire for a few days and had spent some time getting to know the course route and enjoying the Massif Central. We met up at Issoire municipal camp-site Saturday afternoon and set up tents on a quiet pitch some distance from the noisy – pet dog populated – caravan and camper van area. The municipal site took advance bookings but that wouldn’t have been necessary as the bad weather forecast had scared so many people off. It was definitely the best place to be for convenience, being only a kilometre or two from the race start in the morning.

Once the tents were up we went to the registration near the race start area where I had to collect my dossard (race number). This étape was better organised than the previous one in Modane and so it was rapid and straight forward.

We both drove our cars 65km directly to Saint-Flour and dropped mine off there with a key hidden on it – so if I didn’t make it to the end of the race Paul would not be stranded. A warm change of clothing and shoes for each of us was left in the car overnight. We then drove back to Issoire and cooked dinner ourselves after visiting the supermarket. Paul made an excellent blue cheese, ham and mushroom sauce and I cooked some épeutre (old type grain) spaghetti – making an excellent and filling meal giving no one a bad stomach. Bikes were prepared for the morning and a peaceful night was had despite the strong wind and rain. My 35 euro pop-up tent was excellent even in those conditions.

Wake up time on race day was 5am – but I was wide awake before that. Breakfast had been cooked the night before and coffee brewed up and kept in a Thermos flask. Despite good organisation there still seemed to be a shortage of time for getting away – though we were at the race start for 06:25am 20 minutes before the deadline. Fortunately it was not raining at breakfast and the morning preparation was very easy – but it was partly this that gave us the false impression of the day about to unfold and led to a few unfortunate choices of clothing.

In the evening after the race we looked for a restaurant in Issoire centre. Despite the centre being large and populated there was nothing open other than really skanky kebab and pizza shops and they were very numerous. That’s when it hit home how poor this area must really be. It’s quite sad that their big Étape du Tour was such a wash out. With no other options open Paul treated me to a skanky kebab shop meal – but it was very enjoyable and appreciated all the same. Neither of us could eat fast – the extreme physical effort clearly affecting the ability to get food into the stomach even hours later.